Daniel Ellsberg on U.S. Nuclear War Plans

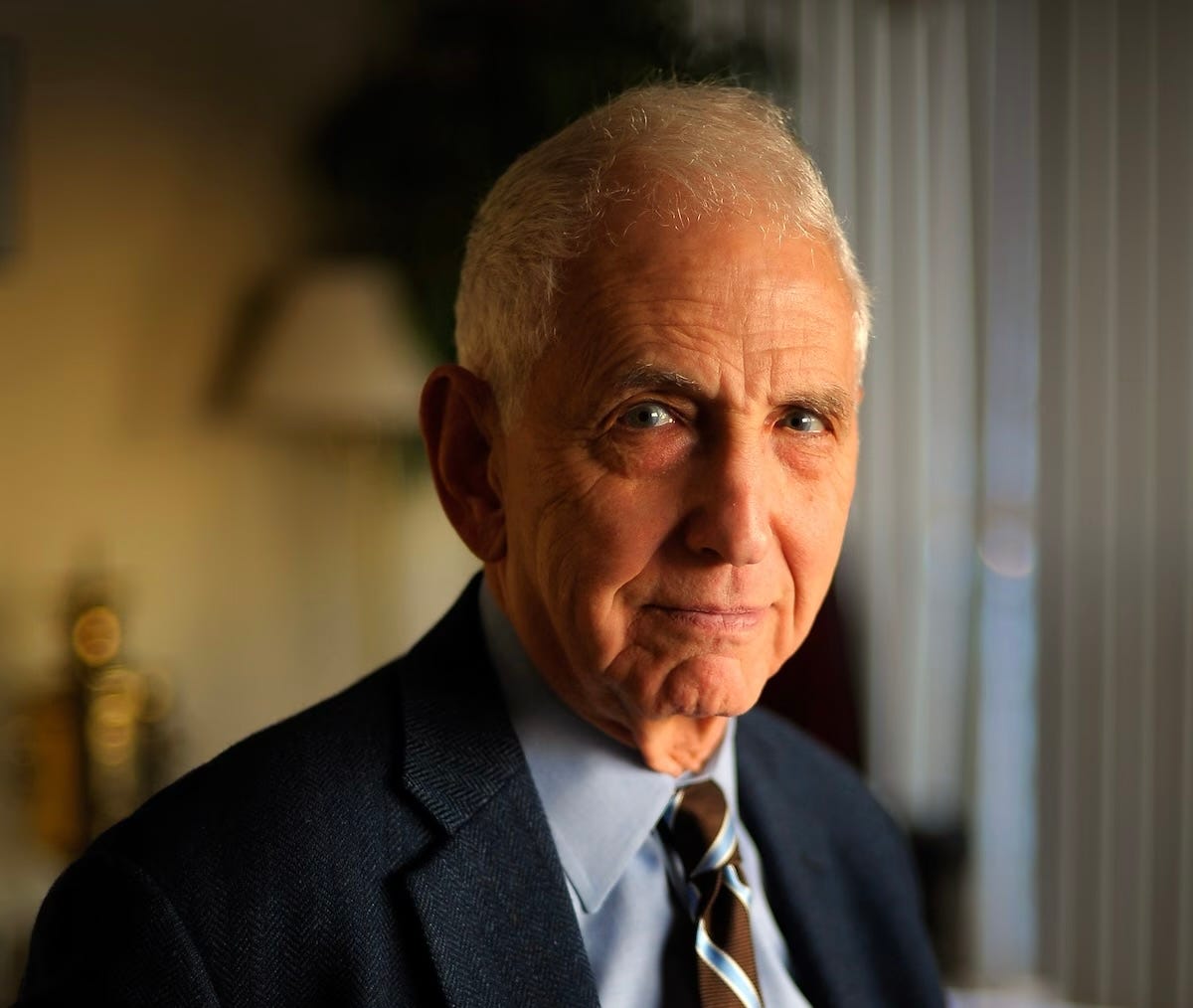

We have lost a great man who performed a valuable service for his country

On June 13, 2019, I drove from San Francisco with my colleague Tom Collina across the Bay Bridge to the Kensington home of Daniel Ellsberg in the Berkeley Hills. It was the 50th anniversary of the publication of the Pentagon Papers.

I was then president of the Ploughshares Fund, a global security foundation, and Tom was policy director. Dan and his wife, Patricia, greeted us warmly on that foggy morning. I had know Dan for some years and it was a pleasure to see him again.

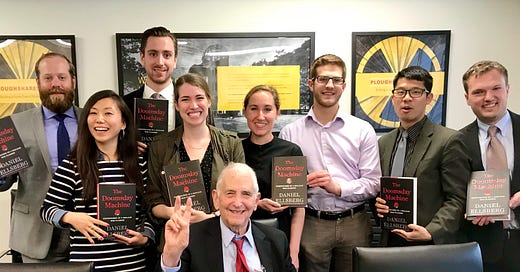

Dan showed us his basement office. It took up a whole floor of his house and was crammed with books, papers, tapes and clippings. Though 88 years old at the time, he was vigorous, sharp and completely engaged in current policy debates, particularly nuclear policy. He had begun his career as a nuclear war planner in the Pentagon. While most know that Dan took a trove of history files on the duplicitous history of U.S. policy in Vietnam, fewer know that he took an even larger amount of files on nuclear war planning. He disclosed these files in his last book, The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner.

After coffee, catching up with each other’s lives and talking about politics and the state of the arms control movements, I pulled out my recording equipment and interviewed Dan for an episode of our podcast, Press the Button. We talked for over an hour and I edited it down for the show.

You can listen to the 25-minute talk here. (The interview begins at the 9 minute and 30 second mark.) Dan described how, after starting as a nuclear war planner in 1958, he came to realize the deep insanity of these plans.

I was working on what we thought was the most urgent problem in the world. And that was how to deter a Soviet surprise attack with the missiles that we thought they had…Air Force intelligence was projecting thousands of missiles in a few years and 300 in a year or two. The reality turned out to be that in 1961 [when the Strategic Command thought they had a thousand], they had four…we had 40. Our estimates were off by a factor of 250.

I don’t think that there were very many Americans, even in the government, who understood fully the scope of what we were planning [to deter a Soviet attack]. In fact, when I fully learned that it made me question my sense of the human species…

I drafted a question that was sent to the Joint Chief in the name of the President: “If your plans are carried out as planned, if they hit the targets that are intended, how many will die in the USSR and China?” It was answered within a week in the form of a graph showing how many millions would be killed immediately. The figure was 275 million people.

I followed up with a question about deaths in other countries and got the answer back within a week in a table with each country listed. Our plans would kill another 100 million in Eastern Europe, the so-called satellite countries, the occupied countries….Not a single warhead would land on our allies in Western Europe, but 100 million of them would be killed by the fallout from the east (depending on the wind). Another 100 million would be killed in countries adjacent to the Soviet Union and China, neutral counties like…Japan and India. A total of 600 million people. Or one hundred Holocausts, as I saw it.

Ellsberg noted that those figures did not include deaths from fire, which is one of the major causes of death but is hard to quantify. Nor does it include deaths from what we now know would be the climate change caused by these attacks. The soot and particulates launched into the atmosphere by nuclear explosions would block out sunlight, killing kill food crops around the world, leading to global mass starvation. He argued that if we had done this then - or if we do it now with reduced but still massive attacks on China or Russia - it would not be Mutual Assured Destruction or MAD, but Self-Assured Destruction, or SAD.

His core argument is that while the concept of deterrence has some merit, we do not need anything close to the numbers of weapons both the U.S. and Russia have in their arsenals. Today, there are roughly 12,500 nuclear weapons in the world, down from about 66,000 at the height of the Cold War. Most are still held by the the Russia (5,900) and the United States (5,245). Scientists estimate that using just a few hundred of them would induce a Nuclear Winter that could kill between one and two billion people.

Listening to Dan’s voice again on this podcast, I am struck by how sensible he is and how absurd are the abstract arguments made in Congress and DOD today to justify thousands of new weapons at an estimated cost of $2 Trillion.

“It’s worth a lifetime worth of effort to avert these nuclear dangers, to dismantle these doomsday machines.” - Dan Ellsberg

Dan agreed with my analysis that nuclear policy is shaped today not by sound strategy or security needs but by the drive for contracts from the handful of companies that make nuclear weapons. The $50 Billion the U.S. spends each year on nuclear weapons is a powerful incentive for making more. He replied:

Absolutely. We would be safer if we spent that money on anything else. Or if we gave the money to Boeing and Lockheed and Northup Grumman to not build the weapons…Pay their workers, maybe retrain them to make solar panels. But don’t continue this process of building and maintaining two Doomsday Machines on high alert that threatens all life on Earth. There must be a way to pay off the people who have been living on government subsidies for the last 70 years in the aerospace industry.

Dan summed up his views, as he often did, with series of Socratic questions.

Is the ability to kill 600 million or a billion people necessary for deterrence? Obviously not.

Can it, therefore, be justifies as a lesser evil, as a necessary evil? No. Under no circumstances whatsoever. Actually launching that force - which we’ve come close to doing many times - just doing what we are planning to do, could never, under any circumstances, be anything other than the greatest evil imaginable.

Could it be moral for either country to launch their force? It is not just immoral, we have no words for it. It would be the most evil act in human history. It would be ending our species.

Could it be moral to threaten to use these weapons? No. The U.S. Catholic Bishops said in a pastoral letter in 1983 that is forbidden to threaten to do what it is forbidden to do. If it is evil to do it; it is evil to threaten to do it…

There is no justification for what we have. Nor for 50 percent of it. Nor for 30 percent of it.

He closed on a positive note. I asked him how optimistic or pessimistic he was that we would find the leaders and generate enough political pressure to reduce global nuclear arsenals.

I am optimistic. I think we have a chance. I think it’s not impossible. What is impossible looking ten years ahead? What was impossible in 1980 was that the Berlin Wall would come down in 1989. That was not unlikely — it was impossible. But it did happen.

There’s no guarantee. It may take a transformation of our values and political economy…But our experience is such that you can’t say it’s impossible. And if it’s possible, it’s worth a lifetime worth of effort to avert these nuclear dangers, to dismantle these doomsday machines.

Dan died on June 16 at the age of 92. Listening to this interview, pulling out these quotes brought me right back to his home, to his crowded office, to his insatiable curiosity and inspiring drive. We would all be lucky to be half as cogent and energetic as Dan was in his later years, or as courageous as he was in his youth. Right up until the day he died he was talking, pushing, hoping. We will miss him

May his memory be a blessing.

Daniel, R.I.P.

As far as I can determine, the last, i.e., most recent, endorsement Ellsberg made was of the Declaration of Public Conscience. Others are invited to follow his lead: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSeh67hNh3Q_j1RBFxJbInFzNyZ7vy3UnL-RMP8FQWJixesQbA/viewform