Strategies for Reducing Nuclear Dangers

It is highly unlikely that in their present state existing pro-arms control efforts can have any meaningful impact on Trump’s nuclear policies.

The concluding Part IV of my new analysis published in the International Policy Journal of the Center for International Policy.

The very first step in avoiding extinction is simply to be aware of the threat.

A re-elected Trump will likely put nuclear weapons programs on steroids, trash the remaining U.S. participation in the global arms control regime, and trigger discussion of new nuclear weapons programs in more other states than we have seen since the early 1960s. Indeed, Trump’s election has intensified talks in some countries that, in a period of uncertain American leadership and growing threats from Russia and China, they need to develop their own nuclear weapons. This is not just adversaries like Iran, but allies like South Korea where a growing majority of the public already favors developing nuclear weapons.

It is unlikely that in their present state, the existing pro-arms control organizations and research programs can have a meaningful impact on Trump’s nuclear policies. Nor is a mass anti-nuclear movement likely to emerge, as it did in the 1980s. There are, however, several possibilities that could develop measurable influence over nuclear policy.

The first and easiest is for the existing groups to merge. As it stands, they are simply too weak to have any discernible political impact, but united they might. There are a few that could continue on their current budgets and funding streams. Most will, at best, limp along as funding grows more constricted. If just a few of the groups could agree to merge efforts, it could snowball. Mergers would increase their size, visibility and clout while reducing administrative overhead.

Similarly, research programs and academic institutes could agree to cooperate on substantive reports documenting the current crisis, its root causes and plans for preserving and modernizing nuclear security agreements. While a report from projects at Stanford, Harvard and Princeton is always valuable, a combined report would generate more interest and produce more impact on policy makers. The same is true for research projects at think tanks, such as the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace or the Brookings Institution.

The recently formed Task Force on Nuclear Proliferation and U.S. National Security is a recent example of such an approach. This centrist group is the result of a collaboration among Harvard University’s Belfer Center, the Carnegie Endowment and the Nuclear Threat Initiative. They hope to issue a report in mid-2025 “with policy recommendations to guide the future of U.S. national security policy.” Whether the Trump White House will listen to such a group is an open question, but it could help develop a consensus among those outside the extremes represented by the incoming administration.

The relative rarity of such cooperation is a testament to the strong institutional reluctance and competition for recognition that motivates most organizations in the field.

Another approach could be for major donors to encourage coordination by funding a new campaign. Several large donors could agree to fund such a campaign headquartered in a single institute (perhaps one not associated with previous efforts), providing grants to experts, advocates and communications mavens conditioned on their participation in a joint effort.

This was the model successfully developed and deployed in the New Start campaign and the Iran Deal coalition in the 2010s. These two campaigns built on the success of similar campaigns in the 1980s to extend and strengthen the Non-Proliferation Treaty, to negotiate the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, and to ratify the Chemical Weapons Convention. Those, in turn, learned from the successful campaign to Save the ABM Treaty in the 1980s.

These formal, cooperative, jointly-funded campaigns are the only ones that have worked absent the kind of mass mobilizations represented by the Nuclear Freeze movement.

All these efforts were three-legged stools, relying on the work and cooperation of experts, who develop and validate alternative nuclear policy; advocates, who work with government officials in the executive and legislative branches to advance the policies; and messengers, who build public support for the policies through sustained media engagement.

Another possible method is for donors to provide grants to add a nuclear weapons or Pentagon budget component to larger, established expert and advocacy groups. This could fit in well with groups looking to protect social programs from Trump’s budget ax, providing an alternative source of budget savings. Stand alone efforts have failed, but an integrated approach may have a better chance of success. This technique worked well for the Iran campaign, bringing in groups such as MoveOn, Indivisible, Vote Vets and J Street who otherwise may not have had the resources to work on the issue.

Finally, if none of the above approaches prove feasible, or if Trump’s hammerlock on the executive and legislative branches is judged too powerful to overcome, a campaign based primarily on communications might work.

Media and Mass Movements

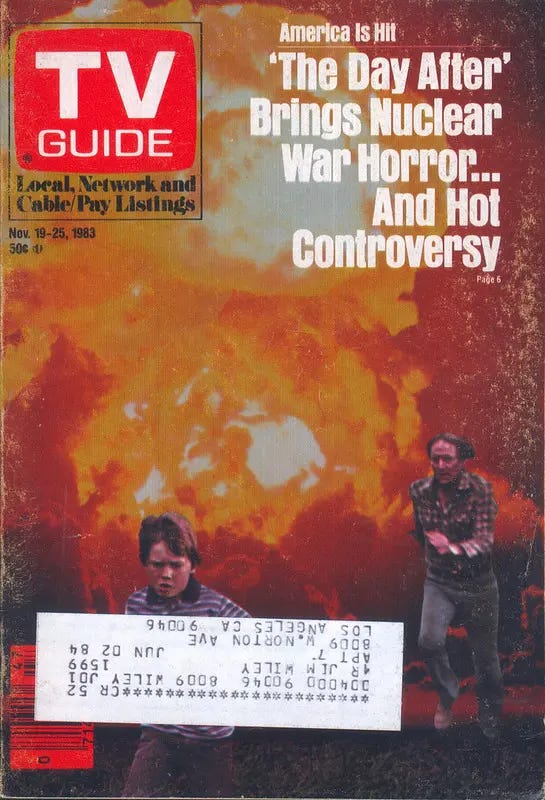

Donors often look to duplicate the impact of the ABC movie event, The Day After. It was one of the most dramatic communications events of the 1990s, said to have even moved President Reagan towards nuclear abolition.

It is possible that one or more such movies could reawaken public concern about nuclear risks. Annie Jacobson’s brilliant 2024 novel, Nuclear War: A Scenario, for example, could be such an event. Dune director Denis Villeneuve has purchased the film rights to the book. “The expectation is that Villeneuve would take this one as another giant project after he completes Dune: Messiah, which he and Legendary are developing as the conclusion of the trilogy,” reports the Hollywood publication, Deadline.

Many thought that the award-winning film, Oppenheimer, could play such a role. While it had a huge impact on audiences, however, it had no such corresponding impact on policy. Nor did it spontaneously generate a new anti-nuclear movement.

The lesson may be that a movie or show has to be part of an existing movement rather than relying on it to instigate such a movement. The Day After aired in 1983 during the Nuclear Freeze movement that had already generated one million people to demonstrate at a rally in Central Park in 1982. Films can validate the concerns of thousands of people already in motion but not generate momentum where none exist.

Absent a mass movement, the value of such a movie could best be realized by coalitions of experts and groups prepared and funded to amplify its message as part of a multi-faceted campaign.

“It’s vital that we use media technology to reverse the direction that we seem to be headed in again,” says David Craig, author of Apocalypse Television: How The Day After Helped End the Cold War. “I don’t think that it’ll be in the form of a one-off Hollywood narrative. It would need to be dozens coming together and letting communities know that this is something that we can’t afford to ignore.”

Alternatively, a big-event film or series could help generate collective action if it came out during a period of heightened media concern over nuclear dangers. Starved of funds, many news organizations could benefit from generous grants to support their investigation of the growing nuclear risks. The Outrider Foundation is engaged in such a strategy with its no-strings grants to The New York Times, the Associated Press and others. The foundation does not dictate the content of the reporting, its grants merely allow journalists to pursue their own analysis.

Conclusion

We are at a critical crossroads. The path forward is not clear. This article is intended to stimulate discussion; it is not meant to be the final word. It is the author’s hope that others will contribute articles correcting this analysis, offering their own, or deepening particular points raised. Others may want to explore why past efforts failed, drawing lessons for future work.

We must start by recognizing that we are in a deep hole. It will take sustained, collective work to get us out and to chart a new course.

More About the Author

Joseph Cirincione was president of Ploughshares Fund for 12 years. He was previously the vice president for national security and international policy at the Center for American Progress; the director of nuclear non-proliferation at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; and a senior fellow and director of the Committee on Nuclear Policy, the Campaign to Reduce Nuclear Dangers and the Campaign for the Non-Proliferation Treaty at the Stimson Center. He worked for nine years on the professional staff of the House Armed Services Committee and the Government Operations Committee. He is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and the author or editor of seven books and over a thousand articles on nuclear policy and national security. He was recently elected vice chair of the Center for International Policy Board of Directors.

End of Part IV

For Part II, please click here

For Part III, please click here

For the complete article, please visit the International Policy Journal at the Center for International Policy.

Bonus: A new article in Gizmodo by Matthew Gault features extensive comments from me and the insightful Sharon Squassoni on all these themes.

Bonus Bonus: A new analysis from the great team at The New York Times covering nuclear issues reads like a mind meld between me and the editorial board. It tracks very closely with the analysis I have presented in Strategy & History this month. Great videos; great analysis.

Here's a strategy for reducing nuclear dangers that is clearly within our reach, as it would cost close to nothing, and depends only upon a will to act.

What if everybody working on nuclear weapons issues at a professional level were writing in one place? Professional experts, activists, engineers, diplomats, and any other nuclear weapons related professionals, all in one place, easily found and accessed by the general public. An online discussion forum would probably be the best vehicle for such a joint effort.

Participating on such a forum would not restrict an expert's ability to continue their writing elsewhere. They could still write their own blogs, books, speeches etc.

What such a forum would do is provide the public with a single place where they could easily access the experts and all of their work. And of course, it would make it easy for the experts to engage each other in public.

The professional nuclear weapons community seems to consider it's job to be to educate and influence policy makers. Ok, great, except for one thing....

We the public are the ultimate policy makers. Democratic institutions are designed to represent the will of the people, so until we the people are successfully engaged, politicians of both parties will continue to ignore nuclear weapons in every national election.

To see the problem being addressed by this post, just look at Substack. There are a handful of nuclear weapons experts writing here. But each of them is acting on their own, writing on their own blog, to very little interest. Neither the business ambitions of the writers, nor the larger question of national survival, are being successfully addressed.

The fact that the nuclear weapons community hasn't figured out how to write together in one place 30 years after the invention of the public Internet provides an example of a failed status quo which is ripe for disruption. If the entire nuclear weapons community were to gather in one place, maybe one or more of these professionals could become the agent of that much needed change.

Very much appreciate the attempt to outline action paths. Most likely will require some terrible scare to make any of them viable.