History of the Nuclear World, Part I

We built The Bomb to stop Hitler. We never thought we would use it.

To help you prepare for the opening of Christopher Nolan’s blockbuster film, Oppenheimer, I am publishing a nuclear history primer. It will be a series of five articles adopted from my book, Bomb Scare: The History and Future of Nuclear Weapons. This short series will provide you with a summary of the history, physics, strategy and politics that combined to create the world’s first atomic bomb — and usher in a terrifying nuclear arms race.

Building the Bomb

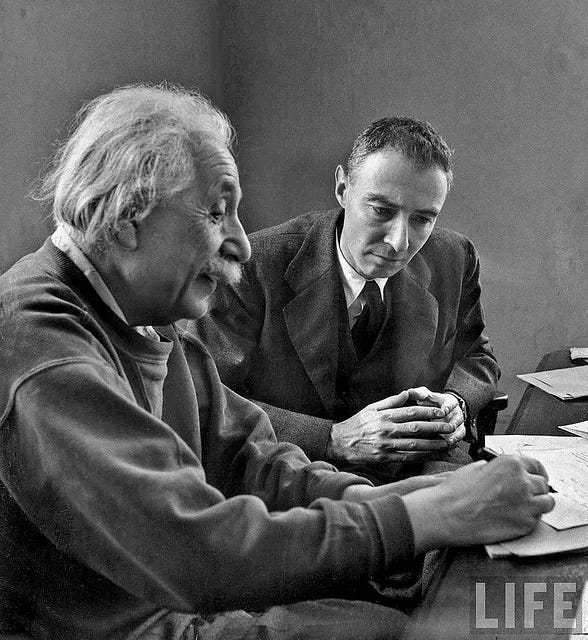

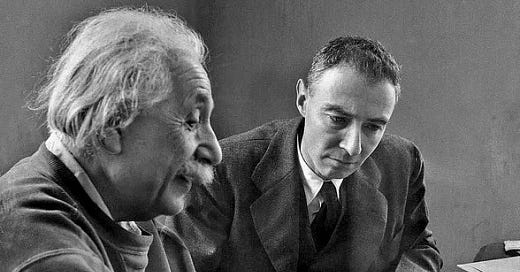

Albert Einstein signed the letter. Years later he would regret it, calling it the one mistake he had made in his life. After the war, he said that "had I known that the Germans would not succeed in developing an atomic bomb, I would have done nothing."

But in August 1939, Adolf Hitler’s armies already occupied Czechoslovakia and Austria and his fascist thugs were arresting Jews and political opponents throughout the Third Reich. Signing the letter seemed vital. His friends and fellow physicists, Leo Szilard and Eugene Wigner, had drafted the note he would now send to President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The scientists had seen their excitement over the recent breakthrough discoveries of the deepest secrets of the atom turn to fear as they realized what unleashing atomic energies could mean. Now the danger could not be denied. The Nazis might be working on a super-weapon; they had to be stopped.

In his famous letter, Einstein warned Roosevelt that in the immediate future, based on new work by Szilard and the Italian physicist Enrico Fermi, “it may become possible to set up a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium, by which vast amounts of power and large quantities of new radium-like elements would be generated.” This “new phenomenon,” he said, could lead to the construction of “extremely powerful bombs of a new type.” Just one of these bombs, “carried by boat and exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port together with some of the surrounding territory.”

The Nazis might already be working on such a bomb. “Germany has actually stopped the sale of uranium from Czechoslovakian mines, which she has taken over,” Einstein reported. He urged Roosevelt to speed up American experimental work by providing government funds and coordinating the work of physicists investigating chain reactions.

“Tt may become possible to set up a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium, by which vast amounts of power and large quantities of new radium-like elements would be generated.”

Roosevelt responded, but tentatively. He formed an Advisory Committee on Uranium to oversee preliminary research on nuclear fission. By the spring of 1940, the committee had allocated only $6,000 to purchase graphite bricks, a critical component of experiments Fermi and Szilard were running at Columbia University. In 1941, however, engineer Vannevar Bush, the president of the Carnegie Institution of Washington and the president’s informal science advisor, convinced Roosevelt to move faster. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill also weighed in, sending the president new, critical studies by scientists in England.

The most important was a memorandum from two German refugee scientists living in England, Otto Frisch and Rudolph Peierls. From their early experiments and calculations, they detailed how vast the potential destructive power of atomic energy could be—and such power’s military implications. Their memo to the British government estimated that the energy liberated from just 5 kilograms of uranium would yield an explosion equal to several thousand tons of dynamite.

This energy is liberated in a small volume, in which it will, for an instant, produce a temperature comparable to that in the interior of the sun. The blast from such an explosion would destroy life in a wide area. The size of this area is difficult to estimate, but it will probably cover the center of a big city.

In addition, some part of the energy set free by the bomb goes to produce radioactive substances, and these will emit very powerful and dangerous radiations. The effects of these radiations is greatest immediately after the explosion, but it decays only gradually and even for days after the explosion any person entering the affected area will be killed.

Some of this radioactivity will be carried along with the wind and will spread the contamination; several miles downwind this may kill people.

The scientists concluded:

If one works on the assumption that Germany is, or will be, in the possession of this weapon, it must be realized that no shelters are available that would be effective and that could be used on a large scale. The most effective reply would be a counter-threat with a similar bomb. Therefore it seems to us important to start production as soon and as rapidly as possible.

They did not, at the time, consider actually using the bomb, as “the bomb could probably not be used without killing large numbers of civilians, and this may make it unsuitable as a weapon for use by this country.” Rather, they thought it necessary to have a bomb to deter German use. This was exactly the reasoning of Einstein, Szilard, and others.

Soon after the Frisch-Peierls memo circulated at the highest levels of the British government, a special committee on uranium , confusingly named the MAUD committee for a British nurse who had worked with the family of Danish physicist Niels Bohr, began assessing their work. The MAUD report on “Use of Uranium for a Bomb” would have an immediate impact on the thinking of both Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt in the summer and fall of 1941. It concluded that a “uranium bomb” could be available in time to help the war effort: “the material for the first bomb could be ready by the end of 1943.” Upon meeting with Vannevar Bush and learning of the MAUD committee’s dramatic conclusions on October 9, 1941, Roosevelt authorized the first atomic bomb project.

“The bomb could probably not be used without killing large numbers of civilians, and this may make it unsuitable as a weapon for use by this country.”

Bush, then head of the newly formed National Defense Research Committee, asked Harvard President James Conant to direct a special panel of the National Academy of Sciences to review all atomic energy studies and experiments. Though Bush’s committee recommended the “urgent development” of the bomb, the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor gave other conventional military concerns greater precedence. It was not until a year later that work began in earnest.

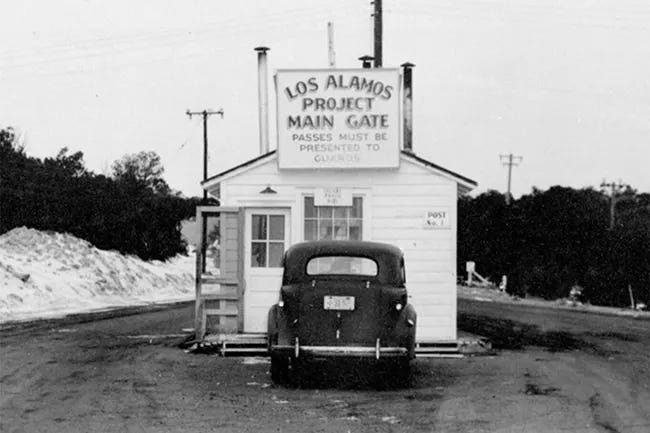

The Manhattan Project, formally the “Manhattan Engineering District,” was created in August 1942 within the Army Corps of Engineers. The laboratory research now became a military pursuit, in part to mask its massive budget. Brigadier General Leslie Groves assumed leadership of the project in September 1942 and immediately accelerated work on all fronts. Historian Robert Norris says of Groves, “Of all the participants in the Manhattan Project, he and he alone was indispensable.”

Groves was the perfect man to direct the massive effort needed to create the raw materials of the bomb, having just finished supervising the construction of the largest office building in the world, the new Pentagon. He needed to find a partner who could mobilize the scientific talent already engaged in extensive nuclear research at laboratories in California, Illinois, and New York. At the University of California at Berkeley, Groves met physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer for the first time and heard his plea for a laboratory purely devoted to work on the bomb itself. Groves thought Oppenheimer “a genius, a real genius,” and soon convinced him to head the scientific effort.

Together they chose a remote southwestern mesa near the town of Los Alamos as the perfect site for the greatest concentration of applied nuclear brainpower the world had ever seen.

To be continued……

This is the first of my five-part series on the science, history and politics of the beginning of the nuclear age, based on my book, Bomb Scare: The History and Future of Nuclear Weapons (Columbia University Press, 2008). I hope you will see the Oppenheimer film and read the other chapters in this story:

Great series. "Atomic" should be "nuclear," but the usage is too entrenched by this point.

The actual use of nuclear weapons by the US against Japan was shaped in part by the moral erosion implicit in the bombing campaigns against both Germany and Japan. The great firebombing raids of 1944 and 1945 against Japan, in particular, were decisive.