History of the Nuclear World, Part V

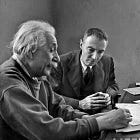

Oppenheimer left us with twin legacies: massive nuclear arsenals and the hope that we can eliminate them.

Robert Oppenheimer anguished over the atomic bomb as soon as he created it. Worse, he spoke publicly about his anguish. Worse, he opposed the development of new and bigger nuclear weapons. That earned him the enmity of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and the conservative Washington establishment. It lead the government committee responsible for nuclear weapons production to humiliate him, as the film Oppenheimer dramatically chronicles, and unjustly to strip him of his security clearances. (A decision recently revoked by the Biden administration.)

The “father of the Atomic Bomb,” failed in his efforts to control what he had created. He was not alone.

Bombs Are Not the Answer

Days after the atomic bombings of Japan, Oppenheimer and other leading scientists in the Manhattan Project wrote a report to the Interim Committee, the government body overseeing post-war nuclear planning. The scientists said that they had no doubt that they could make “weapons quantitatively and qualitatively far more effective than now available.”

But, they warned, they were “unable to outline a program that would assure to this nation for the next decades hegemony in the field of atomic weapons.” They were certain that other nations could build similar bombs and, once they did, “no military countermeasures will be found which will be adequately effective in preventing the delivery of atomic weapons.”

This is still true today. There are many nations that can build nuclear weapons and there is no military defense against them. Thus, the scientists urged, the nation’s security depended on diplomacy, not technology.

We believe that the safety of this nation – as opposed to its ability to inflict damage on an enemy power – cannot lie wholly or even primarily in its scientific or technical prowess. It can be based only on making future wars impossible. It is our unanimous and urgent recommendation to you that, despite the present incomplete exploitation of technical possibilities in this field, all steps be taken, all necessary international arrangements be made, to this one end.

The United States did, indeed, attempt to forge international agreements to control the bomb, even though flawed, as outlined in the fourth article in this series.

After the 1948 coup in Czechoslovakia and the Berlin crisis that same year, however, President Truman ordered an increase in weapons production. By late 1949, the United States had more than 200 atomic bombs. When the Soviets tested their first fission bomb that August, Truman raised the stakes, accelerating a program to build the “Super,” or hydrogen bomb. David Lilienthal, chairman of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), wrote in his diary, “More and better bombs. Where will this lead…is difficult to see. We keep saying, ‘We have no other course’; what we should say is ‘We are not bright enough to see any other course.’”

Many of the scientists responsible for the first nuclear weapon, including Oppenheimer and James Conant, strongly opposed the “Super.” The AEC had asked for the advice of its General Advisory Committee on the entire nuclear weapons program. Oppenheimer and Conant joined in the unanimous opinion of the eight-member group against the hydrogen bomb. They believed it to be a weapon of genocide:

“The use of this weapon would bring about the destruction of innumerable human lives; it is not a weapon which can be used exclusively for the destruction of material installations of military or semi-military purposes. Its use therefore carries much further than the atomic bomb itself the policy of extermination of civilian populations.”

Even if the Soviets developed the H-bomb, they argued, the United States could deter its use with atomic weapons.

The scientists’ views did not prevail. Albert Einstein wrote in March 1950,

“The idea of achieving security through national armaments is, at the present state of military technique, a disastrous illusion. . . . The armament race between the USA and the USSR, originally supposed to be a preventive measure, assumes hysterical character.”

Again, the scientists lost to politics and hubris. Truman feared that he would look weak if he did not build a weapon that the Soviets could build. The majority of U.S. leaders believed that with the new weapons, they could overwhelm the Soviet Union.

The H-Bomb

The Super project inaugurated the design and testing of the advanced weapon that now composes the large majority of modern arsenals.

Fission bombs create temperatures equal to those of the surface of the sun, but fusion bombs truly are the equivalent of bringing a small piece of the sun down to earth. The energy of all stars (including our own sun) comes not from the splitting of atoms, but from their fusion.

The enormous gravity and high temperatures within stars fuses atoms together by overcoming the electromagnetic resistance that keeps them apart. Each fusion releases enormous energies, including the sunlight that makes possible life on earth. The smaller the electrical charge of the atom, the lower the temperature needed to fuse the atoms. Thus, the process in the sun and other stars begins with the fusing of the lightest atoms, hydrogen, into helium, then continues crushing heavier atoms together until they can no longer overcome the resistance of the created atoms.

For the sun, this process has been continuing for about 4.5 billion years and will end some 5–6 billion years hence when most of the its atoms have been fused up the chain into carbon, oxygen, silicon, magnesium, and sulfur. Massive stars, many times the size of our sun, can synthesize atoms all the way to iron before collapsing in a supernova explosion whose shockwave forges trace amounts of the heavier elements up to and including uranium and scatters all these elements into the universe.

Every one of these atoms found on earth was created by this nuclear synthesis. The iron in our blood came from a supernova.

This science was now applied to weapons. Fusion weapons have two or more separate nuclear components in the same device that are ignited in stages—the energy released in the exploding fission “primary” is used to compress and ignite nuclear reactions in the separate fusion “secondary,” vastly increasing the explosive yield. The energy released in these weapons is generated primarily by the fusion of isotopes of hydrogen, hence the name, hydrogen bomb.

The United States tested the first hydrogen device in the southern Pacific Ocean on November 1, 1952. Whereas the first fission nuclear explosion—the Trinity device—had a force of 20,000 metric tons of TNT (that is, 20 kilotons), the first hydrogen explosion had a force of 10,400,000 metric tons of TNT (10.4 megatons).

The Soviet Union tested its first fusion device a year later on August 12, 1953. The American Bravo test of March 1, 1954, exploded the first deliverable H-bomb (with a yield of 15 megatons) and the Soviets dropped their first true H-bomb on November 23, 1955.

Atoms for Peace

America’s leaders were enthusiastic about both nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the 1950s. Expert witnesses told Congress that nuclear energy was the miracle power of the immediate future. They predicted atomic-powered cars, airplanes, and homes. They said that nuclear reactors would make electricity so cheap that we would no longer meter it.

President Dwight Eisenhower also believed in the promise of nuclear energy, but was more worried than many of his subordinates were about the dangers of nuclear weapons. He sought a way to promote peaceful use of the atom while also restricting military use.

On December 8, 1953, Eisenhower stepped to the podium of the United Nations to unveil his Atoms for Peace program. The former general wrote in his diary two days after the speech that he was inspired by “the clear conviction that the world was racing toward catastrophe,” and that he had to act.

Eisenhower explained to the General Assembly, “the knowledge now possessed by several nations will eventually be shared by others—possibly all others.” While countries were already beginning to build warning and defensive systems against nuclear air attack, he cautioned, “Let no one think that the expenditure of vast sums for weapons and systems of defense can guarantee absolute safety for the cities and citizens of any nation. The awful arithmetic of the atomic bomb does not permit any such easy solution.”

Eisenhower proposed the creation of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to promote the peaceful uses of atomic energy while the nuclear powers “began to diminish the potential destructive power of the world’s atomic stockpiles. Eisenhower’s initiative has divided historians into two opposing schools of thought.

“Let no one think that the expenditure of vast sums for weapons and systems of defense can guarantee absolute safety for the cities and citizens of any nation. The awful arithmetic of the atomic bomb does not permit any such easy solution.”

—President Dwight D. Eisenhower

The first group argues that nuclear technology was already beginning to spread, and that Atoms for Peace was the only way for responsible nations to regulate that spread in an attempt to ensure that it would remain peaceful. The second group’s view is just the opposite. As Leonard Weiss, a former Senate staff expert on the program, put it, “It is legitimate to ask whether Atoms for Peace has accelerated proliferation by helping some nations achieve more advanced arsenals earlier than would have otherwise been the case. The jury has been in for some time on this question, and the answer is yes.”

Meanwhile, the U.S. military was equipping their troops with thousands of nuclear weapons, adapting them for use in nuclear depth charges, nuclear torpedoes, nuclear mines, nuclear artillery, and even a nuclear bazooka.

Both the United States and the Soviet Union developed strategies to fight and win a nuclear war, created vast nuclear weapon complexes, and began deploying intercontinental ballistic missiles and fleets of ballistic-missile submarines.

The effective abandonment of international control efforts and the race to build a numerical and then a qualitative nuclear advantage resulted in the American nuclear arsenal mushrooming from just under 400 weapons in 1950 to over 20,000 by 1960. The Soviet arsenal likewise jumped from 5 warheads in 1950 to roughly 1,600 in 1960. The United States was ahead but afraid. As the atomic scientists had warned in the Franck report, numerical superiority did not bring security.

Conclusion

The twin threads of Oppenheimer’s legacy are still with us today. The weapons he helped create continue to pose one of few existential threats to human civilization. His hope for international control and banning of these weapons is still alive.

Indeed, after the nuclear insanity of the first few decades of the Atomic Age, wise leaders forged agreements to limit the arms race and then greatly reduce the arsenals.

From almost 70,000 weapons at the height of the Cold War, we are down to about 12,500 today. That is still enough to destroy human civilization many times over, and new nuclear threats continue to develop. Worse, the decreases have stopped and all nine nuclear-armed nations are developing new weapons and new delivery systems. There are no diplomatic negotiations underway to stop this new arms race.

Over 90 nations, however, have signed a new Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. Vladimir Putin’s threats to use nuclear weapons in his war on Ukraine have once again alerted the world to how easy it is to stumble into nuclear war. Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer film will bring these issues to new audiences in a new way, particularly to that half of the American population under the age of 40 that never experienced the dangers of the Cold War.

We are in our own race, as former Senator Sam Nunn says, between cooperation and catastrophe. We have to hope for and work towards the wisdom of Robert Oppenheimer’s vision. He was almost prophetic in his remarks to a group of Foreign Service officers in 1946 when he said that international control of the bomb was

…the only way in which this country can have security comparable to that which it had in the years before the war. It is the only way in which we will be able to live with bad governments, with new discoveries, with irresponsible governments such as are likely to arise in the next hundred years, without living in fairly constant fear of the surprise use of these weapons.

Amen.

This is the conclusion of my five-part series on the science, history and politics of the beginning of the nuclear age, based on my book, Bomb Scare: The History and Future of Nuclear Weapons (Columbia University Press, 2008). I hope you will see the Oppenheimer film and read the other chapters in this story:

A cringe-free read; well done. (So many summaries cut corners and screw up the details.)

I firmly believe that no account of the Nuclear Age is complete without a tip of the hat to Joseph Rotblat. In early 1945, when the scientists at Los Alamos were briefed on the "destruction"* of the Nazi's nuclear weapon program, they cheered and went back to work on the Bomb. Not Rotblat. That night, recalling that the foremost justification for pursuit of the Bomb was that Germany might get it first, he deduced that the Manhattan Project could be shuttered. The following morning he brought this to the attention of General Groves, who replied, "We are going to build the Bomb, and we are going to drop it." To which Rotblat replied, "I cannot be part of this." and tendered his resignation. His physics career suffered from his independence of mind; he eventual focused in the biological effects of radiation. He and Bertrand Russel founded the Pugwash Movement, on whose behalf he received the 1995 Nobel Peace Prize.

The fundamental question is: Why weren't any (all?) of the other scientists (and military) able to take the same stance?

I will be watching the Oppie the film to see if Rotblat gets a nod.

* In actuality, the German program, deemed impractical given the limited timeframe, had been scrapped two years earlier. As it was the US program delivered only during the final death-throes of the Japanese Empire.

Many thanks.